Defining skin tears

Skin tears are acute, traumatic wounds that have potential to develop into complex and chronic wounds, if not managed appropriately (Idensohn et al, 2019a). It has been shown that they are often under-recognised and under-reported in clinical settings (LeBlanc and Baranoski, 2017; Wounds UK, 2020), which can cause them to be misdiagnosed and mismanaged, resulting in suboptimal intervention and delayed, or inappropriate, treatment. Evidence shows that skin tears often fail to meet the expected wound healing milestones (LeBlanc and Baranoski, 2017). However, with the use of appropriate and often simple preventative measures, skin tears are largely avoidable and respond well to intervention (Mangan and Shoreman, 2021).

It is estimated that the incidence of skin tears is 1.5 million per year (Serra et al, 2018). Prevalence is estimated to vary from 1.1% to 41.2% depending on care setting, with the highest reported prevalence of skin tears in long-term care facilities (Van Tiggelen and Beeckman, 2022). The prevalence and incidence of skin tears is very similar to those of pressure ulcers. However, there is evidence to show that they occur more frequently than pressure ulcers (Carville et al, 2014; LeBlanc et al, 2016; Woo and LeBlanc, 2018). It is important to note that hard-to-heal wounds, including skin tears, have a significant impact on patients’ lives, including prolonged pain, emotional distress, embarrassment, infection and reduced quality of life (Serra et al, 2018).

The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) defines skin tears as ‘traumatic wounds caused by mechanical forces, including removal of adhesives. Severity may vary by depth (not extending through the subcutaneous layer)’ (LeBlanc et al, 2018). Skin tears are also sometimes referred to as cuts, lacerations, grazes and abrasions (Rayner et al, 2015; Jansz et al, 2022); therefore, in some settings, there is a lack of standardised terminology around definitions and classification, which further complicates skin tear management through a lack of standardised documentation and communication (LeBlanc et al, 2018). Skin tears are caused by partial thickness (separation of the epidermis from the dermis) or full thickness (separation of both the epidermis and dermis from underlying structures), and they are sometimes classed as either uncomplicated (heal within 4 weeks) or complicated (chronic [i.e. they fail to heal within 4 weeks]; LeBlanc et al, 2018).

While skin tears most commonly affect the elderly, they can affect people of any age, including newborns (neonates) and very young children (paediatrics), as well as people who are critically and chronically ill (LeBlanc and Baranoski, 2017). In some cases, no apparent cause can be identified; however, skin tears can be caused by a variety of mechanical forces, such as shear and friction, including blunt trauma; falls; poor positioning and handling; transfer techniques; wheelchair/equipment injury; and removal of adherent tapes/dressings (LeBlanc et al, 2018). In addition, the normal ageing process can cause skin to become fragile and vulnerable to damage, and individuals with skin vulnerability are at an increased risk of skin tears (Beeckman et al, 2020). There are both intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors associated with skin tears [Box 1], and focus needs to be on controlling modifiable risk factors, to maintain skin health and avoid injury (LeBlanc and Baranoski, 2017).

Skin tone bias in wound care

Skin changes in people with dark skin tones are not observed quickly enough on a global scale (Dhoonmoon et al, 2021). It has been documented that skin changes associated with ageing, such as ecchymosis and senile purpura, are risk factors for skin tear development (LeBlanc et al, 2021). In dark skin tones, identification of these risk factors is challenging and if preventative measures are not implemented, skin tears may develop. Moreover, research has shown that due to differences in trans-epidermal water loss, dark skin has a lower basal water content (WC) than light skin (Alexis et al, 2021; Peer et al, 2022). It has been suggested that a reduced WC in dark skin may result in differences in vulnerability to pressure ulcers, due to variations in skin biomechanics (Gefen, 2023). These findings may also be applicable to skin tears, which further highlights the need to improve prevention and treatment strategies for skin tears and across different skin tones.

It has been proposed that discrepancies due to skin tone variances may be associated with existing skin assessment protocols being used inaccurately in dark skin (Oozageer Gunowa et al, 2018). Overall, there is a significant lack of knowledge and guidance to support clinicians to identify and manage pressure ulcers in people with dark skin tones.

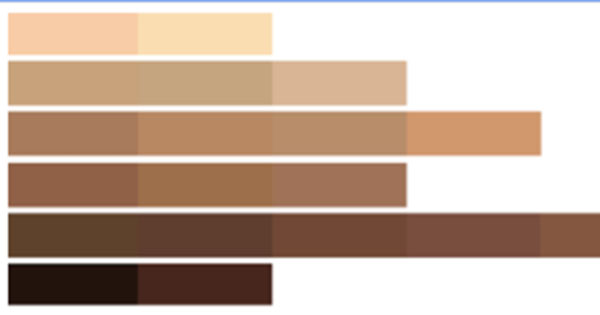

Establishing baseline skin tone is an important part of the initial skin inspection and holistic wound assessment (Dhoonmoon et al, 2021). Since it can be suggested that people with dark skin tones are disadvantaged by a lack of robust evidence-based skin and wound care, use of a validated classification tool should be used to promote accurate assessment and early identification of damage – e.g. the skin tone tool [Figure 1; adapted from Ho and Robinson, 2015].

Individuals from minoritised communities often experience colour-based prejudice or discrimination based on negative references to, or connotations associated with, the colour of their skin, which is known as ‘shadism’, ‘skin tone bias’, ‘colourism’ and ‘pigmentocracy’ (Mswela and Nothling-Slabbert, 2013; Tambala-Kaliati et al, 2021; Aborisade, 2022). Therefore, it is critical that clinicians avoid using metaphors or similes when describing skin tone, such as inappropriately comparing skin tones to food (e.g. cocoa and coffee). Instead, it is recommended that an objective measure and neutral terminology is used, and use of the skin tone tool can support clinicians to consider skin tone variances rather than ethnicity, and to use respectful language when communicating with patients.

Classification of skin tears

No universally accepted classification system exists for skin tears, but tools are available. To meet the need for a user-friendly and simple tool, ISTAP developed the systematic, standardised and validated ISTAP Skin Tear Classification System (LeBlanc et al, 2013), which has been psychometrically tested and classifies skin tears into 3 categories [Figure 2]: type 1 (no skin loss; linear or flap tear which can be repositioned to cover the wound bed), type 2 (partial flap loss; which cannot be repositioned to cover the wound bed), or type 3 (total flap loss; exposing entire wound bed). The validated classification system has been translated into numerous languages, and Van Tiggelen et al (2020) recommend that the ISTAP classification system be adopted into clinical practice as a universal language for describing and documenting skin tears.

Assessing skin tears in dark skin tones

Timely and careful identification of individuals at risk of skin tears is critical, as well as accurate, comprehensive and consistent documentation (Beeckman et al, 2020; Van Tiggelen and Beeckman, 2022). However, there are challenges in assessing skin tears in people with dark skin tones, and there is a need for better education and research. Evidence shows that nurses often have significant gaps in their knowledge about skin tears, and often utilise insufficient prevention measures and inadequate treatment options (Charbonneau et al, 2022). An audit also found a gap in clinicians’ knowledge and management of skin tears in the lower limb (Vernon et al, 2019). It is widely acknowledged that there is a general lack of education on skin tears among clinicians, and there are no clinical studies to date that assess skin tear knowledge in the context of patients with dark skin tones.

Assessing the risk of skin tears in individuals with dark skin tones presents a unique challenge within the field of healthcare. Skin tone diversity is a fundamental aspect of human populations, and it is crucial to acknowledge and understand its implications in relation to assessment of skin health and vulnerability to injury. One of the primary difficulties lies in accurately visualising and recognising subtle changes in the skin’s integrity and colouration [Figure 3]. Traditional methods of skin assessment often rely on visual cues, such as redness, discoloration or changes in skin temperature, to determine potential areas of vulnerability. However, these visual indicators may vary greatly across different skin tones; for example, signs of ecchymosis or senile purpura may be less noticeable in individuals with dark skin tones due to increased melanin pigmentation (Dhoonmoon et al, 2021).

Erythema is traditionally used to detect skin areas that may be infected or have other abnormalities. However, erythema does not always appear as ‘redness’ in many skin tones, especially in those that are dark, and can be missed in the initial assessment (Dhoonmoon et al, 2023). Individuals with dark skin tones can also experience post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, leading to darkened areas around the healed wound site. Although it is usually temporary, this hyperpigmentation can take several months to resolve. Keloid or hypertrophic scarring may also be more common in people with dark skin tones, so wounds need to be monitored closely and appropriate scar management should be provided where necessary.

It is paramount that clinicians assess for other indicators of injury in people with dark skin tones by using both visual and tactile cues – e.g. purple/blue/grey discolouration and change in temperature. Furthermore, full use of the senses – especially touch and hearing (i.e. listening to the patient) – is valuable in the assessment of all patients regardless of the tone of their skin. Clinicians need to ask the patient about their skin and listen to their perspective about what they consider to be a problem – e.g. tightness, changes in feeling/sensation and pain, discomfort or numbness over the affected area.

Another crucial aspect to consider is cultural sensitivity surrounding skin tone and its potential impact on the assessment process. Cultural beliefs, norms and biases can influence how individuals perceive and express their skin health concerns (Buster et al, 2012). Healthcare professionals must be cognisant of these factors and approach the assessment process with empathy and respect to ensure accurate risk evaluation. To address these challenges, healthcare providers need to undergo continuous education and training that emphasises the significance of skin tone diversity in assessing skin tear risk. This includes learning about variations in skin anatomy, understanding the potential limitations of assessment tools, and developing a comprehensive understanding of cultural differences and their impact on patient care (Buster et al, 2012).

Treating skin tears in dark skin tones

A key risk factor for skin tear development is having a history of a skin tear and presentation of skin changes associated with ageing (LeBlanc et al, 2021). Given that these changes may present differently in those with dark skin tones (Dhoonmoon et al, 2021), it is imperative that clinicians are mindful of the subtle changes that may be seen in dark skin tones, recognise associated skin tear risks and implement skin tear prevention programmes.

To guide their clinical decision-making, clinicians must refer to the international best practice guidelines that have been developed for the prevention and treatment of skin tears (LeBlanc et al, 2018). Best practice guidelines help promote standardisation and this is key, since disparities in care often lead to poor assessments and documentation, incorrect diagnosis, ineffective use of treatment pathways and elevated risk of chronicity (Mangan and Shoreman, 2021).

It is critical for clinicians to get wound management right from the first assessment (Guest et al, 2020), as the aim of skin tear management is to minimise the risk of infection and close the wound (Stephen-Haynes and Callaghan, 2017). Assessing baseline skin tone is therefore critical, as well as reviews and reassessments. Treatment of skin tears is multifactorial, and centres around appropriate evidence-based care of the skin, education on skin tears for staff and patients, and regular reassessment (LeBlanc et al, 2018; Rando et al, 2018).

Principles of skin tear management

Treatment and management of skin tears should aim to preserve the skin flap, maintain the surrounding tissue, re-approximate the edges of the wound (without stretching the skin) and reduce risk of infection/further injuries, while considering any comorbidities (LeBlanc et al, 2018). Additionally, initial treatment goals should be to control bleeding, cleanse and debride, manage infection/inflammation, consider moisture balance/exudate control and monitor wound edge/closure [Box 2].

A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for the implementation of a skin breakdown prevention programme, and a wide range of members should be involved – e.g. nurses, clinicians, wound specialists, occupational therapists, physical therapists, social workers, dieticians and pharmacists (Van Tiggelen and Beeckman, 2022). All care settings need to develop and implement a protocol that all members of the clinical team can follow to ensure that consistency is achieved in skin tear management. Evidence shows that implementation strategies, such as a Skin Tear Wound Management Pack or educational programmes for both clinicians and patients, have the potential to promote best practice and early intervention with benefits for patients, including improved quality of life (Mangan and Shoreman, 2021; Jansz et al, 2022).

Patient education

Evidence shows that attitudes and practices of individuals with skin tears can influence their outcomes (Varga et al, 2022). Therefore, it is important for clinicians to involve patients in their own care and educate them on how to recognise age-related changes to their skin, the impact of medications, opportunities for self-management and steps they can take to prevent and manage skin tears. Patients also need to be taught how to be aware of their surroundings, recognise potential risk, monitor their own skin and provide basic first aid if a skin tear does occur – e.g. stop the bleeding, clean the wound, dab the wound instead of rubbing it and avoid adhesives (Deprez and Beeckman, 2022).

Product selection and silicone dressings

ISTAP advocates for special attention to be paid to dressing selection in relation to the management of skin tears (LeBlanc and Woo, 2022). It has been proposed that the ideal dressing for skin tears is easy to remove and apply; does not cause trauma on removal; is non-toxic; provides a protective anti-shear barrier; creates an optimal environment for healing; is flexible and moulds to contours; manages exudate and infection; and can afford extended wear time (Wounds UK, 2022).

Current best practice for the treatment of skin tears recommends use of silicone contact layers and/or silicone foam dressings (LeBlanc et al, 2018). A study found that the use of silicone dressings supports healing and wound closure with expected healing trajectory, quicker time to wound closure and faster mean healing times, as compared to non-silicone dressings (LeBlanc and Woo, 2022). Tips for using silicone-based mesh or silicone foam dressings on skin tears are given in Box 3. Clinicians should consider using dressings that are less adhesive to avoid skin stripping during dressing changes, especially for individuals with sensitive skin. In addition, products that are not recommended for skin tears include iodine-based dressings, hydrocolloid dressings and gauze (Idensohn et al, 2019b).

Conclusion

Skin tears are a significant problem for both patients and the clinicians who treat them. However, clinicians often downplay their effects, and there is a need to reverse the defeatist, underestimated and trivialised view of skin tears. They are a source of pain, distress and anxiety for patients, and since skin changes in people with dark skin tones are not recognised or documented quickly enough on a global scale, these patients face significant disadvantages. Therefore, focus needs to be on increasing awareness and improving delivery of evidence-informed prevention and management strategies, to ensure that all patients with skin tears receive the right care at the right time.

Additionally, research and development efforts should focus on creating inclusive assessment techniques and tools that account for a wide range of skin tones. This includes advancements in imaging technologies, the formulation of standardised assessment guidelines specific to dark skin tones and the integration of diverse skin tone representations in medical education materials. In conclusion, assessing the risk of skin tears in individuals with dark skin tones is a complex task that requires sensitivity, knowledge and equitable care. By acknowledging the unique challenges faced by patients with dark skin tones, investing in research and education, and promoting inclusivity in healthcare practices, we can work towards improving the accuracy and effectiveness of skin tear risk assessment for all individuals.