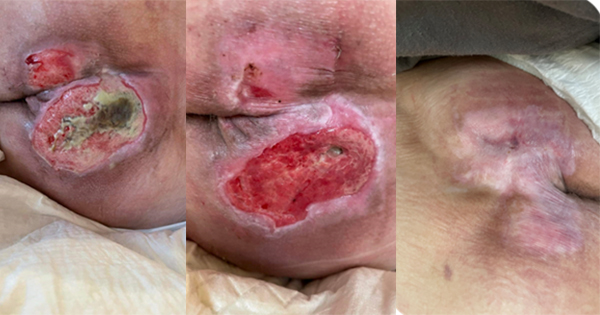

Patients in intensive care units (ICUs) are at high risk of developing pressure ulcers/injuries (PUs/PIs). The DecubICUs study, involving 13,254 patients across 1,117 ICUs in 90 countries, found a prevalence of 26.6% and an incidence of 16.2% (Labeau et al, 2021). PUs have a multifactorial aetiology and dozens of risk indicators have been identified (Coleman et al, 2013; Tayyib et al, 2013; García-Fernández et al, 2014; Bly et al, 2016). Association for PU development was found with factors such as age, haemodynamic instability, impaired tissue oxygenation, haemoglobin, mobility, activity, length of stay (LOS), and diabetes and infections (Ahtiala et al, 2018a; Cox, 2020; Wang et al, 2024, Alderden et al, 2025).

Several risk assessment scales have been developed for ICUs, incorporating different risk factors (Ranzani et al, 2016; Efteli and Güneş, 2020; Ladios-Martin et al, 2020; Wåhlin et al, 2021). While no scale alone suffices, they support clinical judgement and decision-making (Kottner and Coleman, 2023). Risk assessment, combined with skin assessment, should lead to comprehensive prevention strategies (EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, 2019).

The Braden Scale is widely used in ICUs (VanGilder et al, 2017; Mehicic et al, 2024). The Jackson/Cubbin (J/C) scale (Jackson, 1999) was developed specifically for ICU patients. Its predictive properties have been compared to the Braden Scale, and the J/C has demonstrated equal (Delwader et al, 2021) or better performance (Adibelli and Korkmaz, 2019; Higgins et al, 2020). The J/C consists of 12 main categories: age, weight, past medical history, general skin condition, mental condition, mobility, nutrition, hygiene, incontinence and ICU-specific categories, such as respiration, oxygen requirements and haemodynamics. Each scored linearly from one point (highest risk) to four (lowest risk) to describe the clinical risk of PU for ICU patients (Jackson, 1999; Ahtiala et al, 2014). Minor categories include use of blood products and transportation within the hospital, as well as hypothermia — each of which deduct 1 point, meaning increased risk. The lower the score, the higher the PU risk; a total score <29 signifies high risk.

Although the J/C scale is considered viable (Seongsook et al, 2004; Ahtiala et al, 2014; Higgins et al, 2020), it has not gained wide acceptance and requires further validation (Delawder et al, 2021; García-Fernández et al, 2013; Ahtiala et al, 2014). Ahtiala et al (2016, 2018b, 2018c) systematically analysed the Jackson/Cubbin scale and identified additional risk factors not included in existing tools. This comprehensive analysis led to the development of a new, simplified and validated ICU-specific PU risk scale: the Finnish ICU PU risk assessment scale (FiICUs), which significantly outperforms the J/C scale.

Methods

Hospital unit and treated patients

The Turku University Hospital serves as a tertiary hospital for a population of approximately 500,000 inhabitants. The adult ICU has 24 beds and serves as a national centre for hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Both surgical and medical patients needing either high dependency (i.e. step-down unit) or intensive care, are treated. On admission, patients are classified into ICU patients or patients in need of high-dependency care (HDC) based on their treatment needs. The number of adult (>18 years of age) patients treated from 2010-2012 and their PU rates, are presented in Table 1.

The Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (Apache II) score (on the day of admission) and Sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) (daily) are routinely recorded, as well as routine laboratory values. The first PU risk assessment is conducted upon the patient’s admission to the ICU, and subsequently every afternoon. The assessment results are documented in a clinical documentation and information system (Clinisoft, GE Healthcare, USA). The J/C scale was modified slightly (mJ/C scale), to increase its reproducibility (Ahtiala et al, 2014). Fewer points indicates a higher risk of PUs; if the patient scores <29 points (Jackson, 1999; Ahtiala et al, 2014) the risk is considered high or extremely high. At this point, it is advised the patient, at the very least, be transferred onto a mattress suitable for high-risk patients, unless already on one. Otherwise, PU prevention follows general guidelines (NPUAP and EPUAP, 2009), including intensified positioning therapy when appropriate.

Retrospective data collection

The data on patient numbers, characteristics, PU status (all stages of PUs included), SOFA, Apache II and mJ/C scores and their subcategories, LOS (<3 or ≥3 days) and haemoglobin concentration at admission, were retrospectively collected from the clinical documentation and information system by the database administrator, for the years 2010 to 2012.

FiICU scale development

The patient cohort of the year 2010 was used in the development of the FiICU scale. In the 2010 cohort, 25.6% of the patients needed high-dependency care and the rest were ICU patients. Out of the total number of patients, 72% were surgical and 31% were treated for >3 days (average LOS 3.6 days, range <1–64). The treatment time for 77.4% of the patients with PUs was ≥3 days, and 68.6% of patients were sedated.

The subcategory analysis of the J/C risk calculator (Jackson, 1999; Ahtiala et al, 2014) used in 2010 to score linearity and weight (Ahtiala et al, 2016) suggested, after statistical analysis, that incontinence, medical history, oxygen requirement, hygiene, haemodynamics and general skin condition could be developed further as to scoring and content. However, due to hygiene definitions overlapping with mobility and mental condition definitions, this was ruled out. Instead of oxygen input requirement, the more precise measure of tissue oxygenation was used, i.e. partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood by the fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) from the SOFA score (Ahtiala et al, 2018c). Haemoglobin concentration reflects ability for oxygen transport, indicating a risk factor (Tsaras et al, 2016; Ahtiala et al, 2018b). The LOS is considered to be a major risk factor (Theaker et al, 2000; Manzano et al, 2010), which was confirmed in our studies (Ahtiala et al, 2018b; 2018c). The scoring (linearity/weight) of each risk factor was updated (Ahtiala et al, 2016), also taking interactions into consideration, such as LOS and oxygenation, and haemoglobin and PaO2/FiO2 (Ahtiala et al, 2018a; 2018b; 2018c).

Ethics

The study plan was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland (T25/2011, 14.06.2011, §172).

Results

The areas under the ROC curve (AUC) were calculated for both the mJ/C and the FiICU risk scales using first-day points. The AUC for the mJ/C scale was 0.59 and for the FilCU scale was 0.76 in the 2010 population (p<0.0001) [Figure 1] (DeLong et al, 1988). The sensitivity of mJ/C was 58.3, the specificity was 52.4, the positive predictive value (PPV) was 12.8 and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 91.3 for the 2010 population; and the corresponding values for FiICUs (threshold value 20) were 53.0, 83.1, 27.2 and 93.7, respectively.

In 2011, the AUCs for mJ/C and FiICUs were 0.65 and 0.80, respectively, (P<0.0001). In 2012, the respective AUCs were 0.62 and 0.79 (P<0.0001). This was similar to the results of the 2010 population, validating the new scale.

In the whole 3-year population, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV values of the FiICU scale for the whole population 49.5, 84.8, 21.2 and 95.3, and for the high-dependency care patients were 35.5, 90.9, 19.7 and 95.7 and the corresponding values for the intensive care patients were 53.1, 82.5, 21.5 and 95.1, respectively. The risk for PU development increased with the rising score (p<0.0001). For practical purposes, the critically ill patients are categorised into low risk (score ≤12; PU incidence 2.3%, 57% of patients), medium risk (score 13-25; incidence 12%, 34% of patients) and high-risk populations (score ≥26; incidence 26%, 9% of patients) [Table 2].

The patients needing intensive care have more PUs than the patients needing the high-dependency care. Medical patients have twice the incidence of PUs than surgical patients [Table 2].

The new FiICU risk assessment scale is described in Table 3. The minimum score of FiICU scale is zero and maximum score is 62. The measures in FiICUs are inherently independent of interrater variability. An English version of the FiICUs was validated by back-and-forth translations undertaken by medically qualified translators.

Discussion

The J/C scale was considered suitable for PU risk assessment in ICU (Seongsook et al, 2004; Shahin et al, 2007). In 2009, it was chosen with minor modifications (mJ/C) to improve its reproducibility (Ahtiala et al, 2014). However, further analysis was needed (García-Fernández et al, 2013; Ahtiala et al, 2014). A later study (Ahtiala et al, 2016) showed the mJ/C subscores were not linear or equally weighted, contrary to original assumptions (Jackson, 1999).

Of the 12 main categories of the J/C, body mass index, nutrition, respiration, and age did not contribute to PU risk. Mobility and hygiene, though significant, have overlapping and partly irrelevant definitions (Ahtiala et al, 2014; 2016). The same holds for the mental condition involving sedation, which is not an independent PU risk factor (Ahtiala et al, 2018b). The SOFA score’s PaO2/FiO2 subcategory reflects tissue oxygenation better than mJ/C’s oxygen requirement (Ahtiala et al, 2018c). Minor categories like hospital transport (Ahtiala et al, 2016) and hypothermia (Ahtiala et al, 2018d) apply to few patients and are not major predictors. Blood product use is variable and better defined by admission haemoglobin, which also reflects the severity of disease and adverse ICU outcome (Ahtiala et al, 2018b; Chow et al, 2025).

The FiICUs [Table 3] includes four adjusted mJ/C categories: past medical history, skin condition, haemodynamics and incontinence. New categories are admission haemoglobin and oxygenation/PaO2/FiO2. The seventh is ICU length of stay (LOS <3 vs >3 days), an independent PU risk factor (Theaker et al, 2000; Manzano et al, 2010; Ahtiala et al, 2018b).

Although LOS is hard to predict due to patient variability, treatment decisions need to follow condition of each patient. Those in critical care for a longer time are expected to have a greater number of events as the exposure period is longer. The longer the LOS, the more severely ill the patients in intensive care become (Takala et al, 1996; Theaker et al, 2000; Manzano et al, 2010). With an average LOS of only 3.6 days (Ahtiala et al, 2018b) in this unit, it is unlikely that the dichotomy of LOS would excessively influence the FiICUs’ outcome.

The FiICUs, with seven categories, outperformed mJ/C [Figure 1] (Jackson, 1999; Ahtiala et al, 2014), with reproducible and validating results in two independent cohorts (2011, 2012). PU risk assessment tools used in ICUs, and specifically developed for ICU settings, have been tested in highly heterogeneous and sometimes selected patient populations. Their common features include only haemodynamics, skin moisture, mobility and medical history such as diabetes (Ranzani et al, 2016; Efteli and Güneş, 2020; Wåhlin et al, 2021). The COMHON index containing consciousness, mobility, haemodynamics, oxygenation and nutrition (rated from 1 to 4) with rather high interrater reliability is widely used (Uslu et al, 2024).

The great variability in categories makes direct comparison between the tools challenging. This is understandable since not all critically ill patients, even in unfavourable conditions, develop PUs (Inman et al, 1993; Takala et al, 1996). FiICUs integrates the best of the above scales, taking into consideration the current recommendations for comprehensive assessment of systemic and specific risk factors influencing skin integrity. Systemic factors, such as haemodynamic instability and impaired oxygenation need to be monitored as they impact PU/PI development (Picoito et al, 2025; Torsy et al, 2025).

The total PU incidence in this 3-year material was relatively low compared to other studies (Adibelli and Korkmaz, 2019; Efteli and Güneş, 2020; Wåhlin et al, 2021; Labeau et al, 2021). FiICUs’ specificity and negative predictive values are much higher than reported in the previous review for J/C by García-Fernández et al (2013). This combination helps reliably categorise the critically ill patients into populations with different needs regarding preventive interventions. PU development seems to be an independent variable of predicting the risk of death (Ranzani et al, 2016; Ahtiala et al, 2020), making PU prevention essential. This results in the correctly focused use of staff resources and cost-effective use of PU prevention interventions.

Conclusion

The FiICUs is simplified and more precisely defined compared with the previously used the J/C risk assessment scale. The FiICU scale categorises ICU patients into low-, medium- and high-risk groups, which helps allocate resources appropriately to each risk category. Early identification of high-risk patients is crucial to prevent tissue damage before it occurs. The use of risk assessment scales is always combined with skin assessment and the clinical judgment of healthcare professionals.

Limitations of the study

Patients with PUs/PIs on admission (N=115) were excluded since they may be prone to further PU/PI development during their ICU stay, which might induce a bias. Patients with device-related nasal PUs/PIs (N=26) were excluded since their development cannot be predicted with any risk scale. Relevant data for FiICU calculation was not available from 82 non-PU/PI and from 6 PU/PI patients, accounting altogether only 4.7% (229/4899) of the total population, which is probably not enough to affect the conclusions made. The results are based on a retrospective analysis of data from a single centre. However, the results remained the same in three different, large, unselected patient cohorts, minimising the potential bias caused by retrospective analysis from a single centre. Still, confirmatory results from prospective and/or multi-centre validation is needed.