The presence of a BRCA gene mutation has been predicted to increase lifetime risk of breast cancer by 72% for BRCA 1 carriers and 69% for BRCA 2 carriers (Kuchenbaecker et al, 2017), a significant increase when compared to the projected 12% lifetime risk of a woman without this mutation (McCarthy et al, 2017). While the current number of BRCA-positive women is unknown, it is believed that only 5.5% of BRCA carriers in the US have been identified (Drohan et al, 2012). Other gene mutations, such as ATM, PALB2 and CHEK2, are also predicted to increase lifetime breast cancer risk (Collins and Isaacs, 2020; Woods et al, 2020).

Bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy (BRRM) is an option selected by women who seek to proactively manage their elevated risk of breast cancer due to the presence of a genetic mutation. This risk-reducing surgery aims to remove as much breast tissue as possible, effectively lowering lifetime breast cancer risk by 90% (Rebbeck et al, 2004). BRRM has steadily gained in popularity, in part due to increased rates of genetic testing (Liede et al, 2018; Guo et al, 2020). Insurance claims database surveys between 2003 and 2016 found the rate of BRCA-positive women undergoing BRRM increased 1.2–1.6% a month (Liede et al, 2018).

However, BRRM is not without the potential for complications. Infection, wound development, bleeding, and the need for reoperation have been noted following this surgery (Zion et al, 2003; Hunt et al, 2007), as have issues with body image decline, fear of breast cancer occurrence, sexuality and interpersonal relationships (Hallowell et al, 2012; Gopie et al, 2013; Grogan and Mechan, 2017; Glassey et al, 2018a, 2018b; Bai et al, 2019). While lymphoedema development in the upper extremity, breast, chest, and trunk is recognised as a complication of breast cancer survivorship (Armer et al, 2020; Flores et al, 2020; Anbari et al, 2021), it has not been acknowledged in the literature following risk-reducing mastectomy, despite the act of breast removal creating the potential for lymphoedema development (Fu et al, 2009; Liu et al, 2021).

The burden of lymphoedema

Lymphoedema results from a disequilibrium between the microvascular filtration rate of the capillaries and venules and that of the lymphatic drainage system (Mortimer, 1998). Breast cancer-related lymphoedema is characterised by an abnormal accumulation of lymph in the interstitial spaces, leading to persistent swelling in the affected arm, shoulder, neck, breast, trunk, or any combination of these (Nelson, 2016). While this secondary lymphoedema can result from axillary node dissection, it may also occur from sentinel node biopsy or lumpectomy as a component of breast surgery, radiotherapy, or other trauma to the region (Liu et al, 2021). Its development is thought to be multifactorial and influenced by systemic treatment strategies, the individual’s ability to form collateral lymphatic pathways and body mass index (Runowicz et al, 2016; McLaughlin et al, 2020). Additionally, lymphoedema can also occur at any point in a woman’s life after breast cancer treatment, including mastectomy (Anderson and Armer, 2021).

The treatment and self-management of lymphoedema have been found to create a significant physical, psychosocial and economic burden for breast cancer survivors (Fu et al, 2009; Cheville et al, 2020; Lovelace et al, 2019; Pritlove et al, 2019; Armer et al, 2020). Issues with physical immobility, pain, swelling, and compression bandaging interfere with work and leisure activities; such challenges result in a decreased quality of life (Flores et al, 2020; Lytvyn et al, 2020).

Sun et al (2020) also reported on the negative economic impact of compromised work ability due to lymphoedema development. Women in this study reported the inability to work, the need to retire early, or having to adapt work duties due to the limitations caused by lymphoedema. Finally, De Vrieze et al (2020) documented the financial challenges people with lymphoedema face, such as the ongoing costs of treatment, therapy, and supplies across their lifetime.

Aim

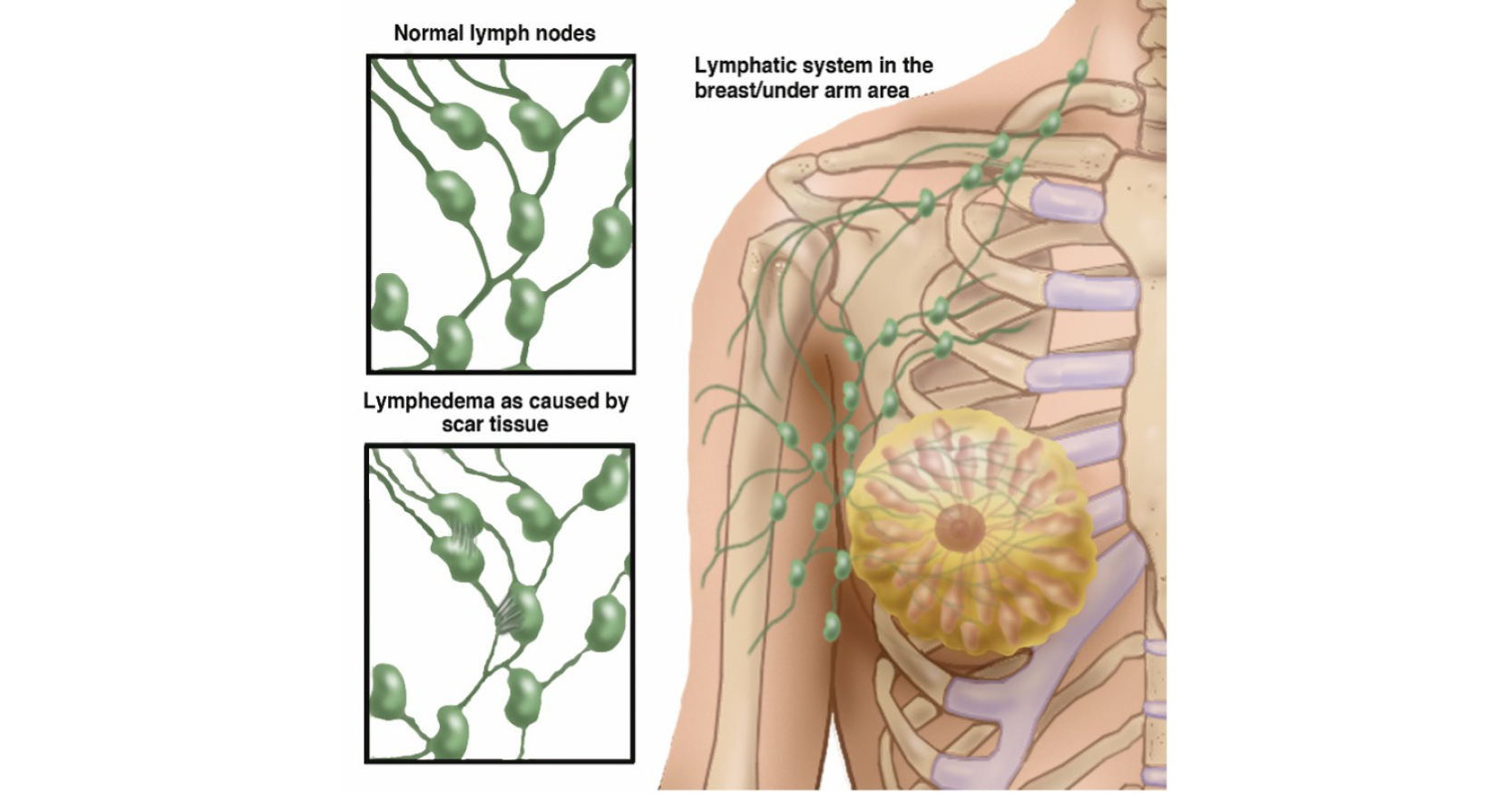

In describing breast cancer-related lymphoedema location and occurrence, the literature focuses on the upper extremity, with other locations such as the breast, chest, and trunk being less well-investigated. This is often due to difficulty in assessing and measuring lymphoedema in these areas (Mayrovitz and Weingrad, 2018). While BRRM does not typically require the removal of lymph nodes, local tissue, including lymphatic vessels, can experience trauma during breast removal (Figure 1). This potentially places a woman at risk of developing secondary lymphoedema following risk-reducing breast removal in her lifetime.

With women making the decision to undergo risk-reducing mastectomy to decrease lifetime breast cancer risk, understanding the incidence of breast, chest and truncal lymphoedema occurring after this prophylactic surgery will serve to inform treatment approaches for this unique population of survivors.

The purpose of this literature review is to understand the reported occurrence of lymphoedema of the breast, chest, and/or trunk following risk-reducing mastectomy in women with an elevated lifetime breast cancer risk.

Methods

Search strategy

For this literature review, a BRRM was considered to be a risk-reducing surgery to remove both breasts, prior to a breast cancer diagnosis, in order to decrease an elevated lifetime breast cancer risk. A contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy was defined as a surgery to remove the unaffected breast after a breast cancer diagnosis.

The following inclusion criteria for searches were selected: previous risk-reducing mastectomy, female assigned gender at birth, and the presence of reported breast, chest, and/or truncal lymphoedema following risk-reducing mastectomy in the non-cancerous breast(s).

Exclusion criteria for this review included: male assigned gender at birth, the diagnosis of lymphoedema in any part of the arm (peripheral lymphoedema) following risk-reducing mastectomy, a breast cancer diagnosis in the mastectomised breast, and prior lymphoedema occurrence in the contralateral breast, chest, and/or trunk.

No studies were excluded based on participant age, study location, type of reconstruction after mastectomy, or if reconstruction occurred.

The preliminary search: bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy and breast, chest, truncal lymphoedema

A health sciences librarian (RG) and a research team member (KP) worked to organise initial search terms and search strategies with an initial focus on risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy and lymphoedema.

The following databases were used: CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (DSR), MEDLINE, PapersFirst, PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science (WOS). These databases were searched between July 2021 and October 2022 then, again in May 2023. No limit was placed on article age during these searches. For each database, search terms were generated after consulting known articles and subject terms surrounding lymphoedema following mastectomy (Armer et al, 2020; Cheville et al, 2020; Liu et al, 2021). The basic search terms set was: lymphedema OR lymphodema OR lymphoedema OR swelling OR edema OR oedema OR linfedema AND (Bilateral risk reducing mastectomy OR bilateral risk reduction mastectomy OR bilateral prophylactic mastectomy OR bilateral risk reducing breast surgery OR bilateral mastectomy OR ((breast surgery or mastectomy) and bilateral)).

A total of 353 records were screened for inclusion from this initial search, 301 from database searching and 52 from backward reference list searching. After the removal of duplicates, 253 records were screened for inclusion (Figure 2). Seventeen articles were assessed for eligibility, each being read through in its entirety. Unfortunately, no articles met the inclusion criteria.

The revised search: contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy and breast, chest, truncal lymphoedema

To ensure a thorough search of the literature, and to gain an understanding of the incidence of lymphoedema occurring in a location other than the upper extremity following risk-reducing mastectomy in the setting of a prior breast cancer diagnosis in the contralateral breast, search terms were revised and broadened. The same seven databases were used as for the preliminary search.

Again, a health sciences librarian (RG) and a research team member (KP) performed the databases searches, which occurred between September 2021 and October 2021 then again in May 2023. No limit was placed on article age during these searches.

The revised basic search terms set created for our second literature search was as follows: lymphedema OR lymphodema OR lymphoedema OR swelling OR edema OR oedema OR linfedema AND (Contralateral risk reducing mastectomy OR contralateral risk reduction mastectomy OR contralateral prophylactic mastectomy OR contralateral risk reducing breast surgery OR contralateral mastectomy OR prophylactic mastectomy OR ((mastectomy/ or prophylactic mastectomy/) AND contralateral)).

A total of 452 records were identified from the databases before removing duplicates, with an additional two articles identified from backward reference searching. A total of 234 records were screened for inclusion (Figure 3). Eleven articles were assessed for eligibility, with each being read in its entirety.

Despite performing a second literature review in which search terms were revised, to broaden and capture articles in which breast, chest and/or truncal lymphoedema occurred following risk-reducing mastectomy in the setting of a previous breast cancer diagnosis, no articles were identified for inclusion in this review.

Results

Despite an extensive review of the literature, including readjusting search terms in order to locate studies on breast, chest, and/or truncal lymphoedema occurrence following bilateral or contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy, no articles were identified for inclusion in this review. A paucity of studies addressed lymphoedema development in the breast, chest and/or trunk, even in women diagnosed with breast cancer.

This may be due to the challenge of evaluating swelling in these areas, with Mayrovitz and Weingrad (2018) and Mazor et al (2019) both reporting difficulty in obtaining accurate measurements of truncal lymphoedema in women who had undergone treatment for breast cancer. Abouelazayem et al (2021) reported similar difficulties in addressing breast lymphoedema following breast cancer treatment due to the absence of standardised diagnostic criteria, a lack of consensus on non-extremity lymphoedema definition, and difficulty in diagnosing breast lymphoedema because of its symptoms being attributed to a treatment side-effect.

Discussion

These sparse findings in the literature surrounding lymphoedema locations other than the upper extremity demonstrate that even in women who have undergone treatment for breast cancer, a gap in the literature exists to address and evaluate lymphoedema occurrence in sites other than the arm. Furthermore, this gap is starkly noticeable among women who have undergone risk-reducing mastectomy as we cannot definitively conclude that lymphoedema of the breast, chest, and/or trunk following risk-reducing mastectomy does not occur based on the dearth of literature.

While this review of the literature did not yield results in identifying breast, chest and/or truncal lymphoedema following risk-reducing mastectomy, it emphasises the importance of addressing this gap. A future study could include a mixed-methods approach using quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews among women who have undergone either bilateral risk-reducing mastectomy or contralateral risk-reducing mastectomy after a breast cancer diagnosis. The experiences of swelling, pain, and/or a decrease in range of motion within the breast, chest, or truncal regions could also be investigated to better understand lymphoedema development in these areas of the body.

Strengths and limitations

This literature review contained both strengths and limitations. As a strength, the discovery of a scant body of literature that met the search criteria was identified. This gap in lymphoedema occurrence in the breast, chest, and/or trunk following risk-reducing mastectomy has been recognised for further study.

An additional strength of this review could be the benefit of raising awareness for the screening and surveillance of breast, chest and/or truncal lymphoedema in the clinical setting for women following risk-reducing mastectomy as more is learned about this phenomenon. The inclusion of an experienced research librarian as a member of the team also contributes to the strengths of the search strategy and the study findings.

As a limitation, due to the uncertainty of genetic factors that may increase a woman’s lifetime risk of breast cancer, our search may be incomplete due to a lack of knowledge. Additionally, the decision to conduct a literature review in which we created our own method of searching with search term sets we selected has increased the risk of encountering bias as we reviewed the literature.

As a final limitation, this review only searched studies published in English and the authors did not search the gray literature.

Conclusion

The literature search reveals an absence of studies evaluating the occurrence of breast, chest and/or truncal lymphoedema in women following risk-reducing mastectomy. Future studies are needed in order to understand if secondary lymphoedema is experienced from tissue trauma following prophylactic breast removal in women with an increased lifetime risk of breast cancer occurrence. Understanding secondary lymphoedema occurrence following risk-reducing mastectomy can serve to identify screening, support, and interventions to promote the mental and physical health across the lifetimes of these survivors.