Wounds have burdened patients and their caregivers since the dawn of humankind (Wernick et al, 2023). They cause a significant economic burden due to their direct and indirect costs (Gupta et al, 2021).

Wound healing is an intricate process that proceeds through the clearly defined, and overlapping sequence of the phases of wound healing (Avishai et al, 2017). This complex process may be impaired at any step along the sequence that leads to delayed healing (Wernick et al, 2023). Chronic and stalled non-healing wounds do not complete some individual stages and are usually stagnated at the early inflammatory stage. (Falanga et al, 2022).

Evidence-based practice in local wound management

There are severe deficits in links between evidence and practice, as well as a high prevalence of ritualistic practice and intuitive decisions often used in practice (Welsh, 2018). Although standardised care based on evidence is crucial to promote adherence to best practices and achieve best outcomes, enhances safety, and improves the overall effectiveness of health care services, there is a tangible inconsistency in wound care standards (Sen, 2024).

Evidence-based dressings play a crucial role in wound care, as they can significantly impact healing outcomes, reduce infection rates, and improve patient comfort (Britto et al, 2017). The ideal wound dressing is designed to meet several critical criteria to ensure that the healing process proceeds smoothly and efficiently and balances essential characteristics to significantly improve outcomes for patients, providing both physical and psychological relief during the healing process (Ferraz, 2025).

Wound care pathways and guidelines are intended to provide a practical evidence-based, step-by-step approach towards wound healing. Complex research evidence can be translated it into simple guides on how to heal wounds to prevent complications and promote healing, changing intuitive based care to evidence based management to actively heal wounds (Dowsett et al, 2021).

Robust evidence has shown that some advanced wound dressings technologies are beneficial in their debriding properties, avoid trauma to new granulation tissue, and enhance cell proliferation and epithelialisation (Shi et al , 2020). There are various debridement techniques that can be used to remove non-viable tissue that prevents the progression of healing.

Autolytic debridement is a process that occurs spontaneously in the body, where phagocytes, leukocytes and proteolytic enzymes target and degrade tissue that has lost its vitality. The non-viable tissue will become softened by autolysis, which will eventually detach from the wound bed (Mayer et al, 2024).

Polyabsorbent fibres

Autolytic continuous debridement can be performed using specific dressings, such as polyabsorbent fibre dressings (Nair et al, 2024). Polyabsorbent fibres (Magnet Technology®, Laboratoires Urgo France) have unique characteristic in reducing wound debris by binding slough (Percival, 2020). The negatively charged fibres in the dressing bond to positively charged regions in slough, which is consequently bound and trapped in the dressing and then painlessly removed when the dressing is removed (Mayer et al, 2024).

A comparative randomised controlled clinical trial was conducted on 159 patients presenting with venous or predominantly venous, mixed aetiology leg ulcers at their sloughy stage (with more than 70% of the wound bed covered with slough at baseline), with the patients followed over a 6-week period (Meaume, et al 2014). The objective was to evaluate the performance of polyabsorbent fibres compared with a hydrofibre dressing. The relative reduction of the wound surface area was very similar; however, the relative reduction of slough was significantly higher in the polyaborbent fibre group than in the control group and the percentage of debrided wounds was also significantly higher. Similar results regarding the debridement of slough were reported in a clinical trial including 50 patients over a 6-week period, presenting with either a venous leg ulcer (VLU) or a stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcer (Meaume et al, 2012a).

Polyabsorbent fibres with silver

Polyabsorbent fibres are also available in a dressing with technology lipido-colloid (TLC) and silver ions (UrgoClean Ag®, TLC-Ag polyabsorbent fibre dressing, Laboratoires Urgo, France). Apart from the fibre characteristic for continuous debridement, the dressing allows atraumatic removal due to the TLC, and antimicrobial action from the silver ions (Trudigan et al, 2014; Adolphus et al, 2016).

In a prospective, multicentre, non-comparative clinical trial, 37 patients with ulcers presenting with inflammatory signs suggesting heavy bacterial colonisation, wounds covered by slough ≥50% of the surface area, were treated with TLC-Ag with polyabsorbent fibre dressing for a maximum period of 4 weeks (Dalac et al, 2016). At the end of the treatment period, the median wound surface area was reduced by 32.5%, the clinical signs of local infection decreased from 4.0 to 2.0, with a 62.5% relative reduction in slough.

A total of 2,270 patients with exuding wounds of different aetiologies at risk of infection or with clinical signs of local infection were managed with the TLC-Ag with polyabsorbent fibre dressing in a real-life observational study (Dissemond et al, 2020). An improvement in healing process There was reported a shortened of healing time after a mean duration of treatment of 22 ± 13 days in 90.6% of cases, along with a reduction in all clinical signs of local infection.

Polyabsorbent fibres with nano-oligosaccharide factor

The TLC-nano-oligosaccharide factor sucrose-octasulphate treatment range (UrgoStart® Treatment Range, TLC-NOSF, Laboratoires Urgo, France) has been shown to have MMP reduction properties, thus supporting faster healing rates of chronic wounds (Münter et al, 2017; Dissemond et al, 2020; Augustin et al, 2021; Meloni et al 2024).

Two prospective, multicentre clinical studies assessed this dressing in the local treatment of VLUs (Sigal et al, 2019). The use of TLC-NOSF with polyabsorbent fibres pad provided substantial improvement in wound area reduction, and the authors concluded that this novel dressing can provide clinicians with effective, safe, and simple solution for wounds at different stages of healing, until wound closure.

A systematic review conducted to identify the clinical evidence available on TLC-NOSF, identified 21 clinical studies, varying from double-blind randomised control trials (Meaume et al, 2012; Edmonds et al, 2018) to real-life observational trials and case series (Munter et al, 2017; Dissemond et al, 2020), involving more than 12,000 patients. The authors concluded that TLC-NOSF treatment range provides an evidence-based solution for the management of wounds, enhancing wound healing, reducing healing times and increasing patients’ health-related quality of life, while being a cost-effective, and even cost-saving, treatment (Nair et al, 2021).

Due to the robust evidence regarding the TLC-NOSF treatment range, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published its first recommendation regarding the use of the treatment range in February 2019 and reiterated in 2023 (NICE, 2023). NICE provided a clear recommendation that using the TLC-NOSF treatment range provides a cost saving option for treatment of patients with VLUs and diabetic foot ulcers. The evidence evaluated showed that this therapy would save an average of £541 per patient, and if applied to all NHS health services, would save £5.4 million per year.

Sequential management with TLC-Ag and TLC-NOSF

Al Humadi et al (2024) presented 15 clinical cases with the sequential treatment of TLC-Ag and TLC-NOSF dressings. The authors concluded that, although these cases represent a small cohort, the results and clinician feedback support the case that these dressings can be implemented as part of an evidence-based standard of care.

Vidja et al (2024) also reported the results of the same sequential management in 10 clinical cases and similarly concluded that the results achieved in all cases were satisfactory, with a rapid reduction of clinical signs of infection, slough, exudate and pain, and a rapid wound closure, with no adverse events reported during the course of treatment. The sequential treatment may help to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients by resolving these wounds in a shorter period.

Manowska and Szumna (2024) published the implementation of sequential management with three initial cases in Poland, and the positive results obtained also substantiated the findings obtained in large-scale studies and concur the conclusions of the two previous publications.

Evaluation of polyabsorbent fibre dressings

An evaluation of the different polyabsorbent fibre dressings available in the management of diverse wounds was conducted by Gonçalves that advocate of evidence-based practice in managing her patients with challenging wounds. Taking in consideration the robust body of evidence behind the polyabsorbent fibre dressings, the author initiated the evaluation of the different polyabsorbent fibre dressings available in the management of diverse wounds in her hospital.

A review of this evaluation is presented in the case series below, highlighting the insights gained from her real-life experience regarding the optimal dressing choice for her patients.

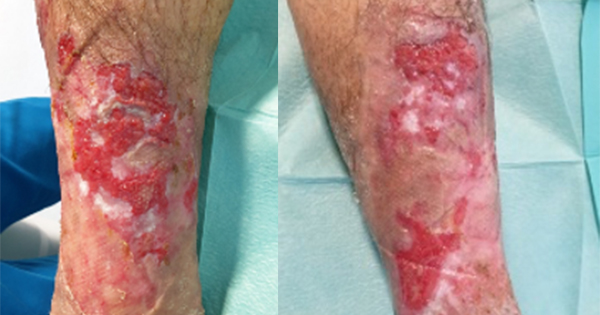

Case 1: A 55-year-old man, with a significant history of cardiac and cardiovascular disease (hypertension, MI, coronary artery bypass graft [CABG], aortic and mitral valve replacement), chronic venous insufficiency and he continuous to smoke, presented with a 12-month-old VLU at the tibialis anterior incision of the external malleolus, previously managed at primary care with different dressings including hydrofibre Ag and povidone-iodine mesh, without any real improvement [Figure 1A].

TLC-NOSF dressing with polyabsorbent fibres (UrgoStart Plus pad, Laboratoires Urgo, Chenove, France) was initiated as the primary dressing in combination with multi-component compression therapy (UrgoK2®, Laboratoires Urgo), changed every 3 days. Within 15 days (four dressing changes), the wound area was reduced significantly [Figure 1B]. At this point, TLC-NOSF Contact Layer was used as the primary dressing and compression was continued, with changes every 5 days. The wound was healed within 4 weeks, a total of seven dressing changes since starting the treatment with the TLC-NOSF treatment range and multicomponent compression [Figure 1C].

A patient with multiple comorbidities with a wound that had been present for a year, had his wound resolved with a combination of evidence-based management within 1 month.

Case 2: A 68-year-old man with significant cardiovascular disease (hypertension, dyslipidemia, peripheral artery disease [PAD], MI), type 2 diabetes, prostatic disease and obesity. He presented with diabetic foot ulcer on the right hallux that had been present for several months, managed with various dressings (not specified) in primary care, but without any progress [Figure 2A]. After a positive probe to bone test, an MRI was done and ruled out osteomyelitis.

Sharp debridement was not possible due to PAD, hypocoagulation and pain. Therefore, it was opted to mange this wound with conservative debridement by means of a polyabsorbent fibre dressing (Magnet Fibre Technology®, UrgoClean®, Laboratoires Urgo) which was held in situ by a cotton bandage not to exert any pressure on the foot. It was decided to use the neutral polyabsorbent fibre dressing instead of the antimicrobial version as there was no indication of local infection. Cleansing was done with normal saline. The dressing was changed every 3 days.

Within 6 days (two dressing changes) the wound bed appeared healthier [Figure 2B], and the local management was changed to TLC-NOSF dressing with polyabsorbent fibres (UrgoStart Plus pad) and cotton bandage, with dressing changes every 4 days. The wound was almost closed after 15 days [Figure 2C].

At this point, the patient was transferred from the nursing home and continued the same treatment with primary health care. The wound was completely healed within a further 2 weeks.

Although this wouund might look simple, the complexity here is the comorbidities of the patient, notably the PAD. The presence of PAD is associated with non-healing ulcers and major amputation (Meloni et al, 2021).

Case 3: A 64-year-old man, with a significant past cardiovascular history (hypertension, MI, CABG of 4 vessels) on anticoagulation. He also had type 2 diabetes, peripheral venous disease and obesity.

He was referred for the management of a pressure ulcer on the heel with signs and symptoms of local infection, that had been present for 6 months [Figure 3A]. Patient was started on pain management. As sharp debridement was contraindicated due to hypocoagulation, TLC-Ag dressing with polyabsorbent fibres (UrgoClean Ag, Laboratoires Urgo) was applied as the primary dressing to aid in desloughing and infection management, with dressing changes on alternate days. Cleansing was done with normal saline, and a secondary dressing of polyurethane foam border was applied. Within 4 days, there was reduction in pain (from 9/10 to 7/10 Pain Numeric Score), a decrease in exudate, periwound maceration and slough with more granulation tissue present [Figure 3B]. The same treatment was continued. Within 3 weeks, the wound was looking healthier with a marked decrease in reported pain (4/10) [Figure 3C].

At this point, local wound management was changed to TLC-NOSF border dressing which was changed twice a week. The wound was almost completely healed within 100 days with TLC-NOSF dressing with polyabsorbent fibres.

Wound closure was achieved in four months for this large pressure injury in a patient presenting multiple comorbidities. By means of implementing the sequential management with TLC-Ag and TLC-NOSF dressings, the wound was conservatively debrided, pain was reduced, and an amputation was avoided, which would have put this patient at considerable risk of further morbidity and potentially mortality.

Case 4: A 62-year-old male smoker with past cardiovascular history (HTN, MI, CABG of 3 vessels and aortic valve replacement), type 2 diabetes and peripheral venous disease. He presented with a deep second degree burn on his sacral region and left buttock, caused by a grounding pad. By 2 days after the injury, the wound was mostly covered with dry, devitalised tissue and was causing a high level of pain. Ibuprofen was started for pain management and the wound was managed with hydrogel for autolytic debridement.

After another two days the level of pain was still high (9/10), and the wound was mostly covered with slough that was difficult to remove [Figure 4A]. It was decided to initiate local treatment with TLC-Ag dressing with polyabsorbent fibres (UrgoClean Ag) for continuous debridement and as the wound was at high risk of infection due to the anatomical location, with dressing changes every 2 days. Within 2 days (1 dressing change), there was a marked reduction in reported pain (5/10), wound bed was mostly covered with granulation tissue and epithelialisation, and reduction of the wound surface area [Figure 4B]. At this point, the local treatment was changed to TLC-NOSF border (UrgoStart Plus Border®), with dressing changes every 4 days. Within another 4 days, the wound was showing progress [Figure 4C], with no pain being reported, but still presented with fragile epithelialisation. In order to protect this fragile skin, TLC-NOSF Contact Layer was used as the primary dressing and the wound was closed within another 4 days (one further dressing change).

In this case, although the patient was again a high-risk for impaired healing, this wound may be considered as an acute wound. However, management with hydrogel did not provide any positive outcomes, and with the management with the TLC-Ag dressing with polyabsorbent fibres and the TLC-NOSF, the wound was resolved in a timely manner. It is also important to note the quick pain reduction in this case.

Case 5: A 40-year-old man, with a strong cardiovascular background (HTN, CCF, LVAD), type 2 diabetes, renal failure, with seven months of hospitalisation in ICU and cardiology, including multiple surgeries in this period, septic shock, hypocoagulation and multiple infected wounds (drains exit-site; sternotomy). Patient was a candidate for heart transplant, but the procedure could not be performed due to high pulmonary hypertension.

The sternal wound could not be approximated and healed by primary intention. Therefore, negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) was initiated and continued for 75 days [Figure 5A]. The therapy was also a source of pain for the patient. At this point, the decision was taken to start local wound treatment with TLC-NOSF dressing with polyabsorbent fibres, held in situ with a secondary dressing of gauze and surgical paper tape, with dressing changes every 4 days. Within 8 days (2 dressing changes), there was a reduction in the wound bed area [Figure 5B]. Dressing changes continued with the same protocol, and the wound was closed within 45 days (11 dressing changes) [Figure 5C].

This was a patient at high risk of impaired wound healing who was managed with NPWT without the desired outcomes and causing pain for the patient. Once the protocol was changed to TLC-NOSF dressing with polyabsorbent fibres a timely resolution could be noted in this complex wound.

Conclusion

The choice of a wound dressing should be based on the wound characteristics, using the clinician’s own experience, but also taking into consideration the clinical evidence supporting this dressing.

The evaluation of the dressings used in these cases was triggered by the robust evidence behind them and recommendations from expert bodies.

Although this is a small cohort, the results obtained were very positive and in line with the results seen in other clinical studies. The addition of these dressings has already been shown to have beneficial outcomes in these type of patients and further evaluation will be continued to reinforce their appropriate implementation in standard of care.